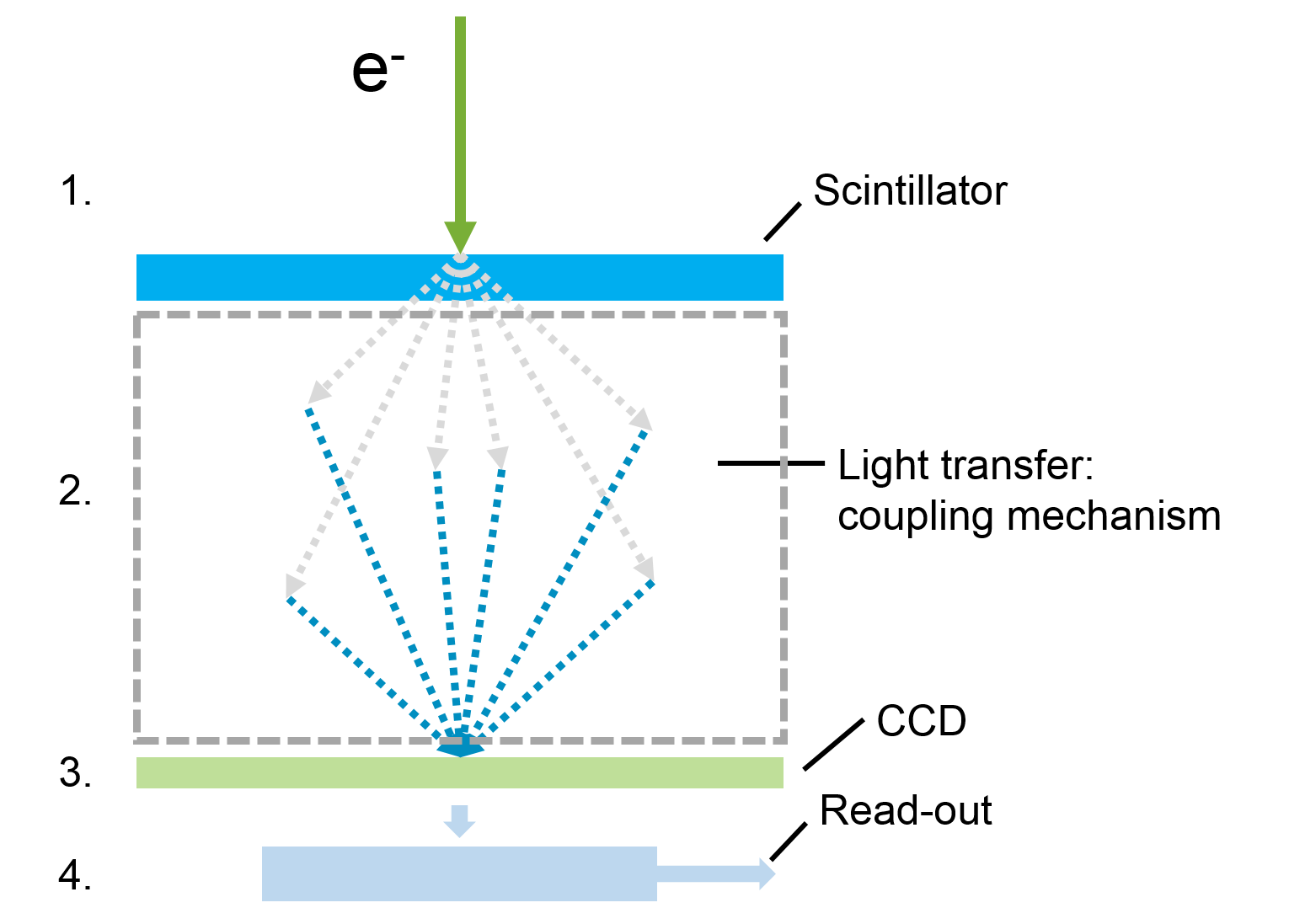

There are a number of options and technologies available for digital imaging in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) applications today. Traditionally, high energy electrons could not be directly exposed to a sensor without excessively damaging the detector. As a consequence, conventional TEM cameras first expose the incoming electron beam to a scintillating film that converts the electrons into light (photons). These photons are then transferred to the sensor, either through a series of optical lenses or a coupled fiber optic plate. Finally, the light is collected by a sensor where the image is created pixel-by-pixel based on the amount of light detected at each position in the sensor.

Conventional TEM image detection architecture

There are four basic steps in TEM imaging to address incoming electrons:

There are four basic steps in TEM imaging to address incoming electrons:

- Convert electrons to signal

- Transfer signal

- Detect signal with sensor

- Electronically transfer signal and read-out to form image

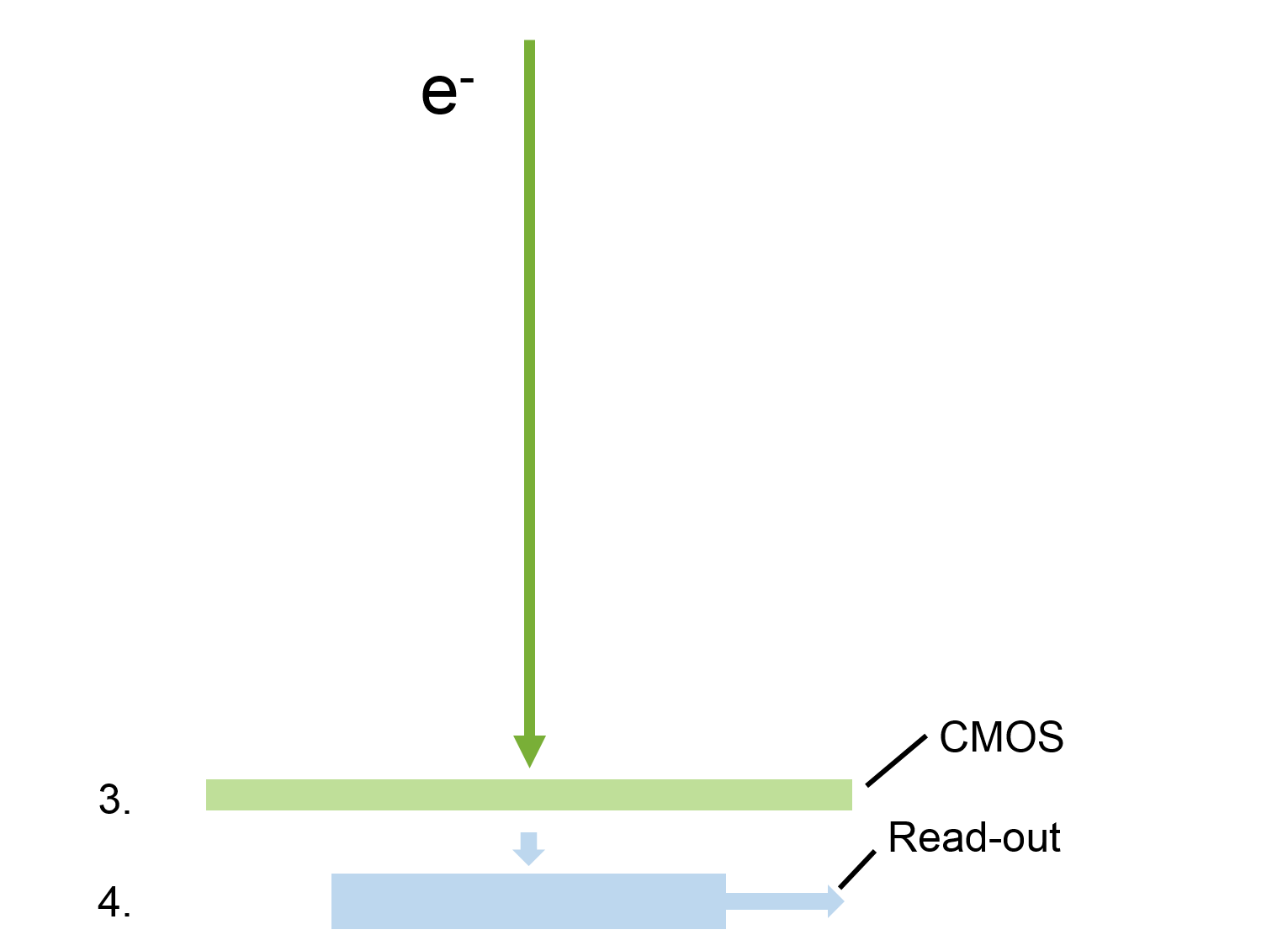

What is different with direct detection?

There are only two steps in TEM imaging with direct detection:

- Convert electrons to signal – not applicable

- Transfer signal – not applicable

- Detect signal with sensor

- Electronically transfer signal and read-out to form image

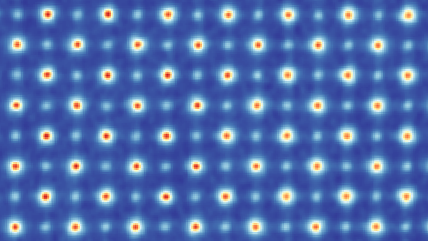

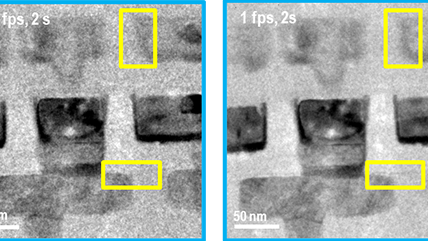

One key difference between conventional and direct detection is a custom CMOS sensor that utilizes the only radiation-hard architecture that can tolerate direct exposure to high-energy particles. To add, extremely high-speed electronics for data transfer and processing enable low-dose counting and super-resolution capabilities. Combined, this allows frame rates (4k x 4k) of 400 frames per second (fps) to be processed in real-time to achieve optimal results.

Convert electrons to signal Transfer signal Detect signal with sensor Transfer signal and read-out image

Step 1) Convert electrons to signal

Gatan uses proprietary phosphor scintillators to optimize signal conversion that enhances detector sensitivity (SENS) and resolution. When you select a scintillator, it is appropriate to know the performance trade-offs between SENS and resolution.

- Sensitivity (signal): Ideal for dose-sensitive use cases where you need to generate more photons per incoming electron (e.g., cryo-tomography, beam-sensitive materials)

- Resolution (spatial detail): Favorable for applications where you require more information to resolve details, but you can increase the dose (signal) without harming the sample (e.g., semiconductors and other less-sensitive materials)

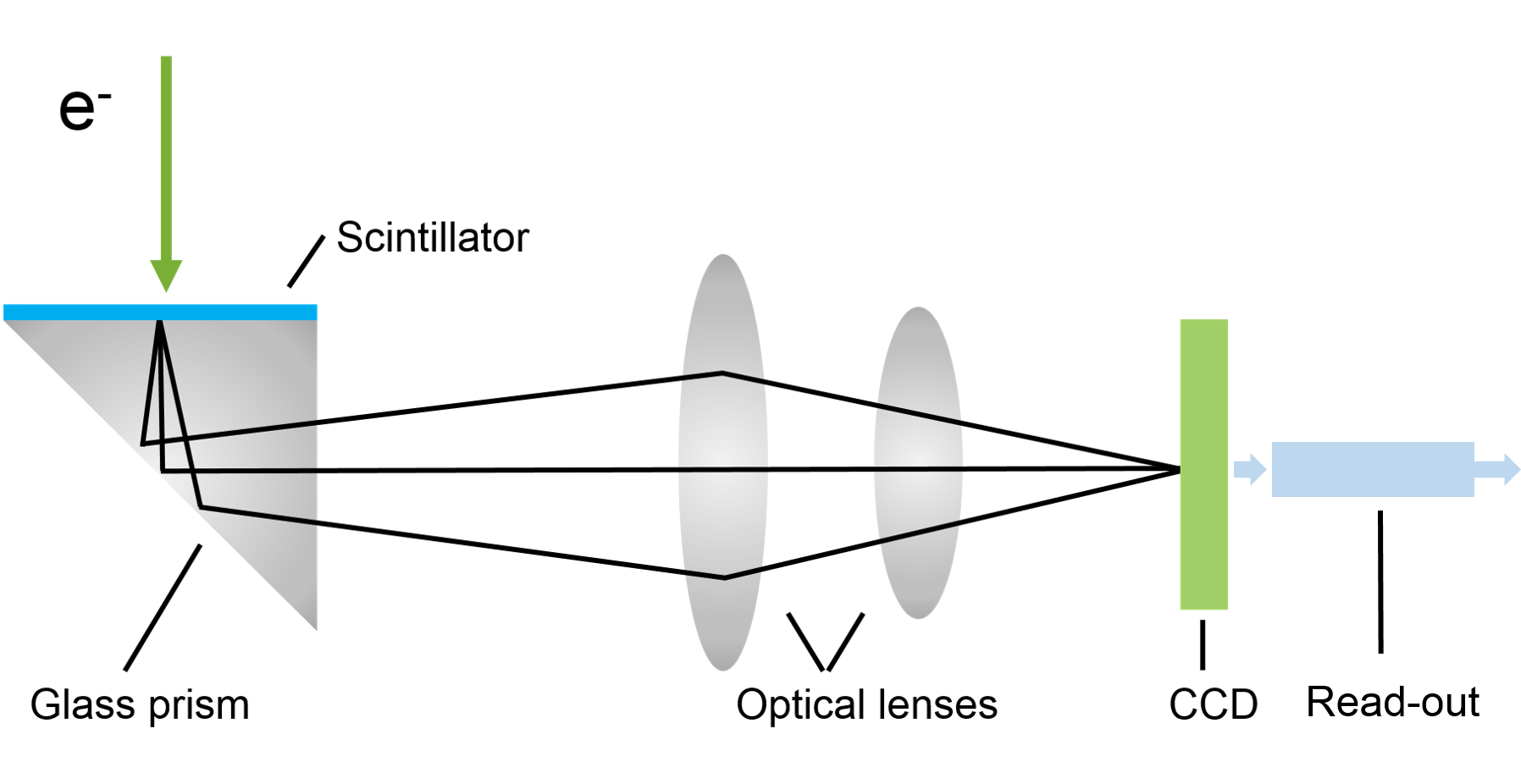

Step 2) Transfer signal

Various coupling (lens- and fiber-coupled) mechanisms are available to optimize signal transfer and meet cost or performance targets for a given detector.

Lens-coupled: Lens optics transmit light to the sensor, where it is converted into sensor electrons (signal)

- Pros: (Gatan) Uses real transmission scintillator; can be less expensive than higher-performance fibers

- Cons: Light (information) loss with lensing, angular dependencies (<10% efficient); vignetting (light fall-off); image distortion for higher magnification

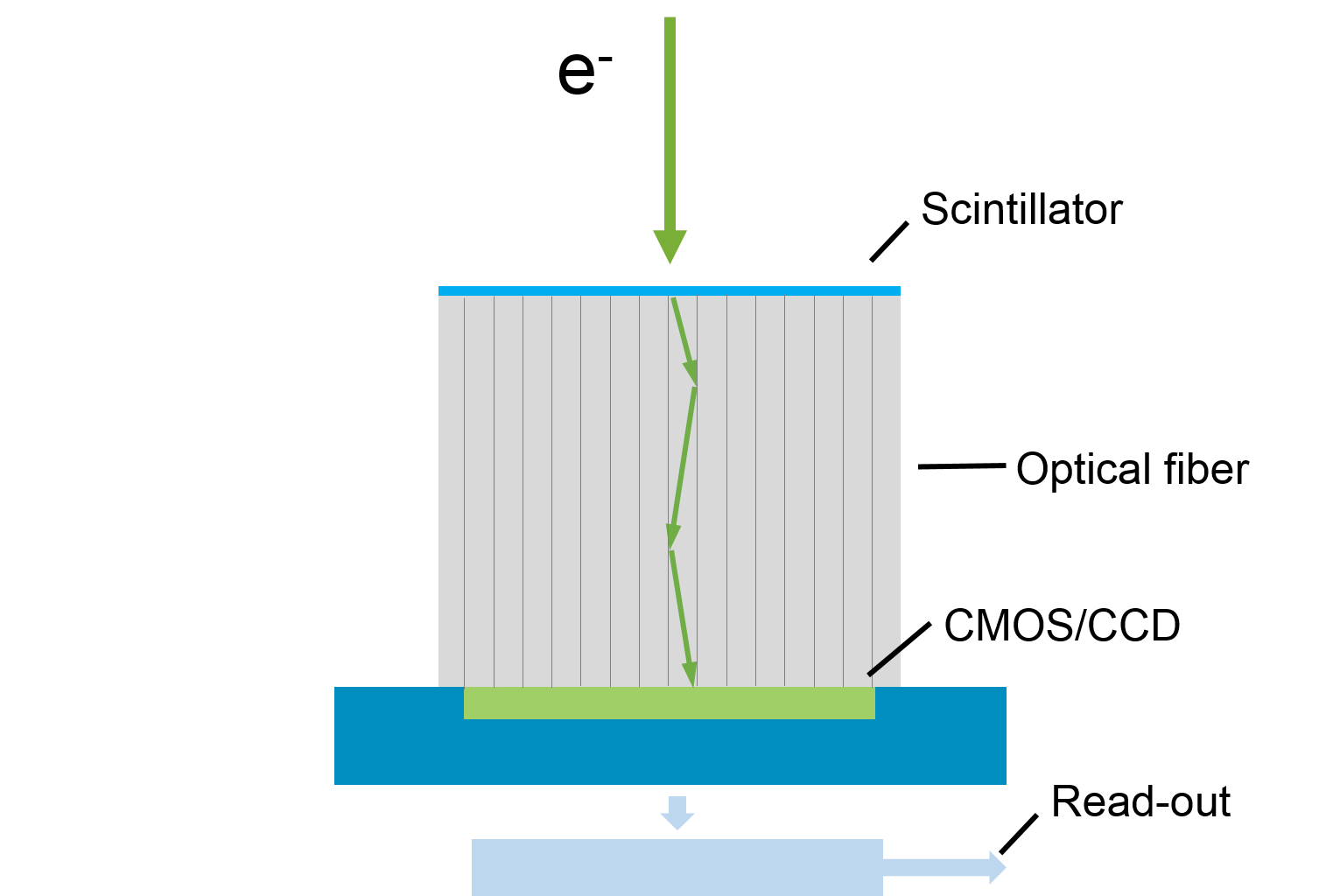

Fiber-coupled: Scintillator creates photons that subsequently create sensor electrons; fiber directly transmits light to the sensor with high efficiency

- Pros: Most efficient transmission of light information to the sensor (1:1 coupling of scintillator:sensor (>50% efficient) with no image distortion); can trade-off SENS verses resolution (fiber configuration detail)

- Cons: Fiber optics are slightly higher cost; requires process optimization including cladding, sintering, and bonding of fibers (Gatan proprietary)

Step 3) Detect the signal with the sensor

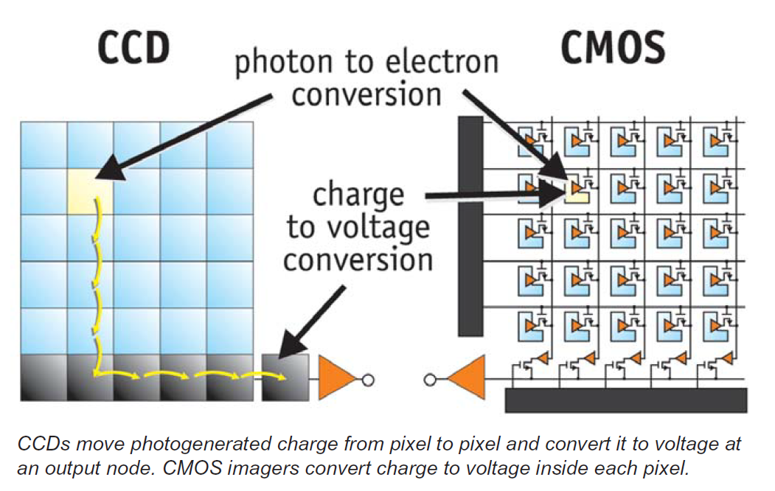

Sensor type (CCD vs. CMOS) offers significant trade-offs for TEM camera performance as there are fundamental differences in architecture.

- Charge-coupled device (CCD): Charge transfers between neighboring cells, and read-out (e.g., noise) is seen at the final stage; binning minimizes the impact of read-out noise

- Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS): Charge immediately converts to voltage (read-out with digital output); supports high frame rates, low overall electronics noise

Both technologies possess inherent advantages, so the question arises about what unique performance characteristics arise from each choice. CCDs can have a 100% fill factor that captures all incoming light, whereas part of the CMOS sensor is occupied by transistors and metal wiring associated with each pixel. Historically, CCDs provided higher-quality images with low noise at affordable prices. Recent design advancements and processing techniques now advance CMOS sensor performance so it is a viable choice for some applications. Note that CCDs still maintain an advantage for binning in terms of signal-to-noise. However, CMOS chips can scale the number of read-out ports and achieve very high frame rates.

Step 4) Transfer signal and read-out image

When a charge converts to voltage, you typically generate noise

- CCD: Transfer data out of the serial register

- CMOS: Converts to voltage per pixel

It is very important to optimize read-out noise (higher voltages) and speed (multi-port and fast read times) for CCDs.

- Optimize controller for low read-noise; leverage multi-port read-outs for faster speed

- Interline CCDs with binning have the fastest readouts (fps) – up to 30 fps due to 100% duty cycle

CMOS typically is seen as a fast sensor because you can run in rolling shutter mode verses the slow global shutter mode.

The cutting-edge counting camera for groundbreaking imaging, diffraction, and in-situ studies.

The only fully integrated hybrid-pixel electron detector with the Gatan Microscopy Suite software for advanced electron diffraction studies.

Gatan’s latest CMOS camera that with its resolution, speed, and ease of use will revolutionize electron microscopy.

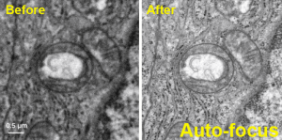

Facilitate your HREM assays by automatically adjusting the critical imaging parameters of a TEM microscope focus, stigmation, and beam tilt.

DigitalMicrograph, also known as Gatan Microscopy Suite, drives your digital cameras and surrounding components to support key applications including tomography, in-situ, spectrum and diffraction imaging, plus more.

Delivers the efficiency and high-throughput data collection that you expect from Latitude software to MicroED studies.

Digital beam control and image processing to enhance the photographic quality of your digital images.

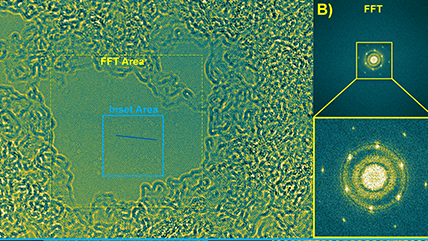

Diffraction analysis package (DIFPACK) to automate the selection area of your electron diffraction (SAED) patterns and high resolution lattice images of crystalline samples.

A powerful tool that expands the utility of your Gatan camera to address 4D STEM diffraction studies.

Sets a new standard for the efficient, high-throughput collection of low-dose, single-particle, cryo-EM datasets from Gatan’s cameras.

The high-performance scintillator camera that elevates your everyday transmission electron microscopy

-

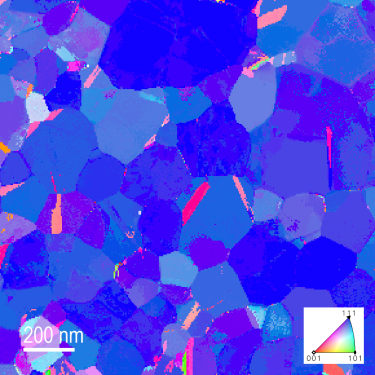

Orientation map generated with STEMx OIM

Orientation map generated with STEMx OIM

-

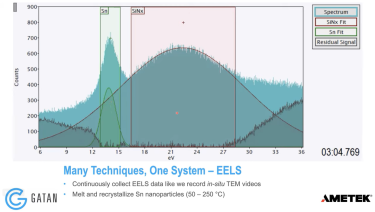

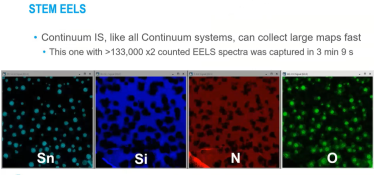

GIF Continuum K3 IS: Advanced Direct Detection for In-Situ Chemical Analysis

GIF Continuum K3 IS: Advanced Direct Detection for In-Situ Chemical Analysis

-

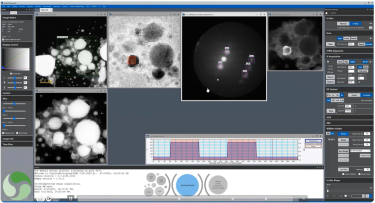

Capturing, Processing, and Synchronizing In-Situ EELS Data

Capturing, Processing, and Synchronizing In-Situ EELS Data

-

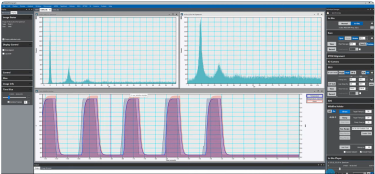

Continuum IS: Versatile time-resolved data collection webinar

Continuum IS: Versatile time-resolved data collection webinar

-

Continuously acquired 4D STEM and EELS spectrum images for in-situ microscopy webinar

Continuously acquired 4D STEM and EELS spectrum images for in-situ microscopy webinar

-

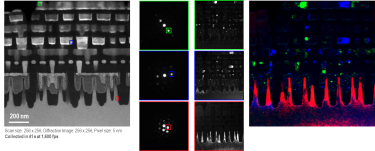

4D STEM and Virtual Aperture Imaging with ClearView

4D STEM and Virtual Aperture Imaging with ClearView

-

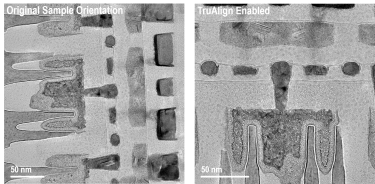

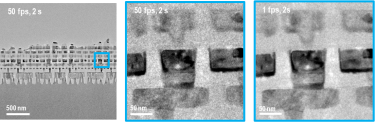

Image samples at the desired orientation with TruAlign

Image samples at the desired orientation with TruAlign

-

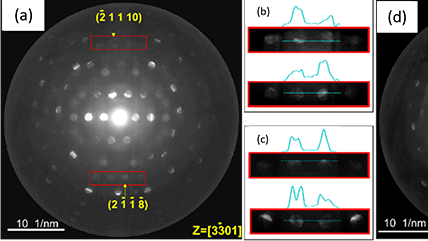

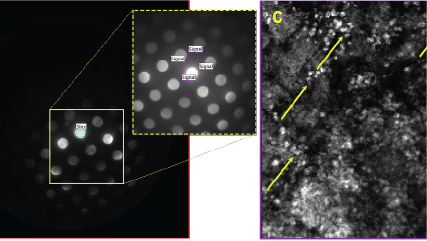

Better resolve faint, high-resolution diffraction spots with ClearView Frame Control mode

Better resolve faint, high-resolution diffraction spots with ClearView Frame Control mode

-

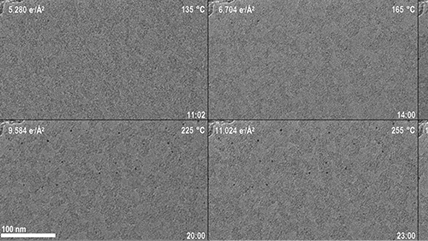

High signal-to-noise TEM imaging with ClearView Frame Control mode

High signal-to-noise TEM imaging with ClearView Frame Control mode

-

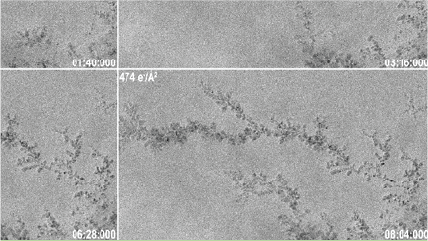

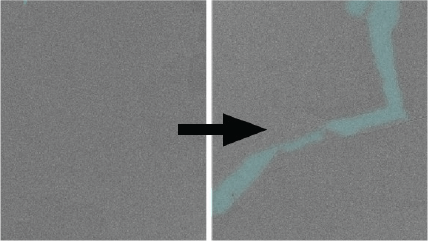

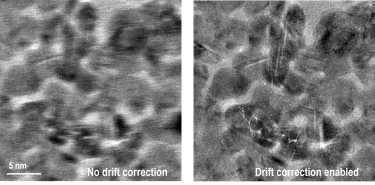

Live drift correction during imaging acquisition

Live drift correction during imaging acquisition

In situ structural analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike reveals flexibility mediated by three hinges

Turoňová, B.; Sikora, M.; Schürmann, C.; Hagen, W. J. H.; Welsch, S.; Blanc, F. E. C.; von Bülow, S.; Gecht, M.; Bagola, K.; Hörner, C.; van Zandbergen, G.; Landry, J.; de Azevedo, N. T. D.; Mosalaganti, S.; Schwarz, A.; Covino, R.; Mühlebach, M. D.; Hummer, G.; Locker, J. K.; Beck, M.

Molecular architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 virus

Yao, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, N.; Xu, Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Weng, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Cheng, L,; Shi, D.; Lu, X.; Lei, J.; Crispin, M.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Li, S.

Tai, C. L.; Chiu, Y. N.; Chen, C. J.; Lin, S. K.; Lin, H. C.; Misra, R. D. K.; Yang, Y. L.; Hsiao, C. N.; Tsao, C. S.; Chung, T. F.

Nondeterministic dynamics in the η-to-θ phase transition of alumina nanoparticles

Sakakibara, M.; Hanaya, M.; Nakamuro, T.; Nakamura, E.

Strain effects in SrHfO3 films grown by hybrid molecular beam epitaxy

Gemperline, P. T.; Thind, A. S.; Tang, C.; Sterbinsky, G. E.; Kiefer, B.; Jin, W.; Klie, R. F.; Comes, R. B.

Multi-convergence-angle ptychography with simultaneous strong contrast and high resolution

Mao, W.; Zhang, W.; Huang, C.; Zhou, L.; Kim, J. S.; Gao, S.; Lei, Y.; Wu, X.; Hu, Y.; Pei, X.; Fang, W.; Liu, X.; Song, J.; Fan, C.; Nie, Y.; Kirkland, A. I.; Wang, P.

Chen, Y.; Chou, T. -C.; Fang, C. -H.; Lu, C. -Y.; Hsiao, C. -N.; Hsu, W. -T.; Chen, C. -C.

Reassessing chain tilt in the lamellar crystals of polyethylene

Kanomi, S.; Marubayashi, H.; Miyata, T.; Jinnai, H.

Hogan-Lamarre, P.; Luo, Y.; Bücker, R.; Miller, R. J. D.; Zou, X.

Electron-counting MicroED data with the K2 and K3 direct electron detectors

Clabbers, M. T. B.; Martynawycz, M. W.; Hattne, J.; Nannenga, B. L.; Gonen, T.

Yang, T.; Xua, H.; Zoua, X.

Intermetallic nanocrystal discovery through modulation of atom stacking hierarchy

Du, J. S.; Dravid, V. P.; Mirkin, C. A.

Hölzel, H.; Lee, S.; Amsharov, K.; Jux, N.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.; Lungerich, D.

Kuwahara, M.; Mizuno, L.; Yokoi, R.; Morishita, H.; Ishida, T.; Saitoh, K.; Tanaka, N.; Kuwahara, S.; Agemura, T.

Organic crystal growth: Hierarchical self-assembly involving nonclassical and classical steps

Biran, I.; Rosenne, S.; Weissman, H.; Tsarfati, Y.; Houben, L.; Rybtchinski. B.

Vanacore, G. M.;Chrastina, D.; Scalise, E.; Barbisan, L.; Ballabio, A.; Mauceri, M.; Via, F. L.; Capitani, G.; Crippa, D.; Marzegalli, A.; Bergamaschini. R.; Miglio. L.

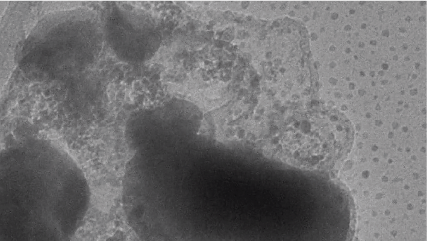

Deagglomeration of DNA nanomedicine carriers using controlled ultrasonication

Hinchliffe, B. A.; Turner, P.; J. H. Cant, D.; De Santis, E.; Aggarwal, P.; Harris, R.; Templeton, D.; Shard, A. G.; Hodnett, M.; Minelli, C.

Three-dimensional electron ptychography of organic–inorganic hybrid nanostructures

Ding, Z.; Gao, S.; Fang, W.; Huang, C.; Zhou, L.; Pei, X.; Liu, X.; Pan, X.; Fan, C.; Kirkland, A. I.; Wang, P.

How to get something out of nothing (almost!): Extracting information from noisy data

Crozier, P. A.

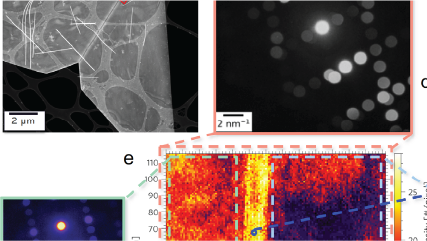

The performance of detectors for diffraction-based studies in (S)TEM

Pakzad, A.; dos Reis. R. D.

Orris, B.; Huynh, K. W.; Ammirati, M.; Han, S.; Bolaños, B.; Carmody, J.; Petroski, M. D.; Bosbach, B.; Shields, D. J.; Stivers, J. T.

Structural analysis of the basal state of the Artemis:DNA-PKcs complex

Watanabe, G.; Lieber, M. R.; Williams, D. R.

Shimizu, T.; Lungerich, D.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Hasegawa, S.; Masuda, S.; Takano, S.; Harano, K.; Tsukuda, T.

Liu, D.; Kowashi, S.; Nakamuro, T.; Lungerich, D.; Yamanouchi, K.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Metastable hexagonal close-packed palladium hydride in liquid cell TEM

Hong, J.; Bae, J. -H.; Jo, H.; Park, H. -Y.; Lee, S.; Hong, S. J.; Chun, H.; Cho, M. K.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Son, Y.; Jin, H.; Suh, J. -Y.; Kim, S. -C.; Roh, H. -K.; Lee, K. H.; Kim, H. -S.; Chung, K. Y.; Yoon, C. W.; Lee, K.; Kim, S. H.; Ahn, J. -P.; Baik, H.; Kim, G. H.; Han, B.; Jin, S.; Hyeon, T.; Park, J.; Son, C. Y.; Yang, Y.; Lee, Y. -S.; Yoo, S. J.; Chun, D. W.

Potential nanoscale sources of decoherence in niobium based transmon Qubit architectures

Murthy, A. A.; Das, P. M.; Ribet, S. M.; Kopas, C.; Lee, J.; Reagor, M. J.; Zhou, L.; Kramer, M. J.; Hersam, M. C.; Checchin, M.; Grassellino, A.; dos Reis, R.; Dravid, V. P.; Romanenko, A.

High-density switchable skyrmion-like polar nanodomains integrated on silicon

Han, L.; Addiego, C.; Prokhorenko, S.; Wang, M.; Fu, H.; Nahas, Y.; Yan, X.; Cai, S.; Wei, T.; Fang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ji, D.; Guo, W.; Gu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Bellaiche, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, D.; Nie, Y.; Pan, X.

Imaging of isotope diffusion using atomic-scale vibrational spectroscopy

Senga, R.; Lin, Y. -C.; Morishita, S.; Kato, R.; Yamada, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Suenaga, K.

Liu, D.; Kowashi, S.; Nakamuro, T.; Lungerich, D.; Yamanouchi, K.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Kim, S. C.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, Y. K.; Oyakhire, S. T.; Yang, Y.; Cui, Y.

The giant Mimivirus 1.2 Mb genome is elegantly organized into a 30 nm helical protein shield

Villalta, A.; Schmitt, A.; Estrozi, L. F.; Quemin, E. R. J.; Alempic, J. -M.; Lartigue, A.; Pražák, V.; Belmudes, L.; Vasishtan, D.; Colmant, A. M. G.; Honoré, F. A.; Couté, Y.; Grünewald, K.; Abergel, C.

Donohue, J.; Zeltmann, S. E.; Bustillo, K. C.; Savitzky, B.; Jones, M. A.; Meyers, G.; Ophus, C.; Minor, A. M.

Lattice-resolution, dynamic imaging of hydrogen absorption into bimetallic AgPd nanoparticles

Angell, D. K.; Bourgeois, B.; Vadai, M.; Dionne, J. A.

Suspension electrolyte with modified Li+ solvation environment for lithium metal batteries

Kim, M. S.; Zhang, Z.; Rudnicki, P. E.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Oyakhire, S. T.; Chen, Y.; Kim, S. C.; Zhang, W.; Boyle, D. T.; Kong, X.; Xu, R.; Huang, Z.; Huang, W.; Bent, S. F.; Wang, L. -W.; Qin, J.; Bao, Z.; Cui , Y.

Rational solvent molecule tuning for high-performance lithium metal battery electrolytes

Yu, Z.; Rudnicki, P. E.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Celik, H.; Oyakhire, S. T.; Chen, Y.; Kong, X.; Kim, S. C.; Xiao, X.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Kamat, G. A.; Kim, M. S.; Bent, S. F.; Qin, J.; Cui, Y.; Bao, Z.

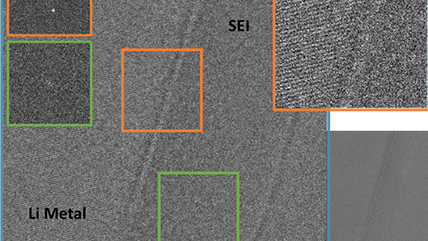

Capturing the swelling of solid-electrolyte interphase in lithium metal batteries

Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Oyakhire, S. T.; Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Boyle, D. T.; Huang, W.; Ye, Y.; Chen, H.; Wan, J.; Bao, Z.; Chiu, W.; Cui, Y.

Electric field control of chirality

Behera, P.; May, M. A.; Gomez-Ortiz, F.; Susarla, S.; Das, S.; Nelson, C. T.; Caretta, L.; Hsu, S. -L.; McCarter, M. R.; Savitzky, B. H.; Barnard, E. S.; Raja, A.; Hong, Z.; Garcia-Fernandez, P.; Lovesey, S. W.; Van der Laan, G.; Ercius, P.; Ophus, C.; Martin, L. W.; Junquera, J.; Raschke, M. B.; Ramesh, R.

Spinterface induced modification in magnetic properties in Co40F e40B20/fullerene bilayers

Sharangi, P.; Pandey, E.; Mohanty,S.; Nayak, S.; Bedanta, S.

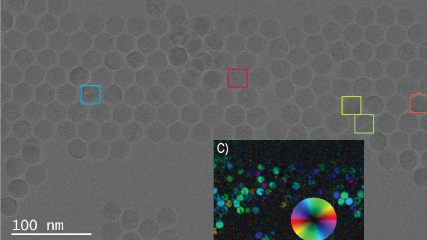

Automated crystal orientation mapping in py4DSTEM using sparse correlation matching

Ophus, C.; Zeltmann, S. E.; Bruefach, A.; Rakowski, A.; Savitzky, B. H.; Minor, A. M.; Scott, M. C.

De novo synthesis of free-standing flexible 2-D intercalated nanofilm uniform over tens of cm2

Ravat, P.; Uchida, H.; Sekine, R.; Kamei, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Konovalov, O.; Tanaka, M.; Yamada, T.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

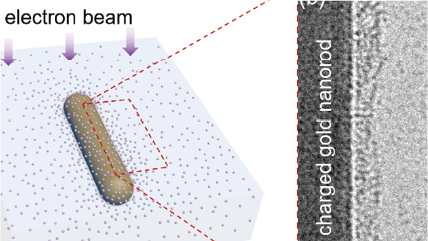

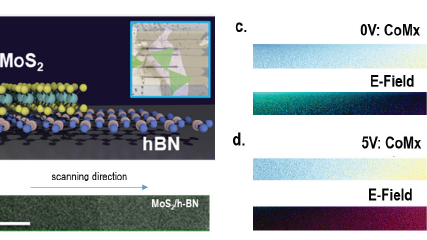

Spatial mapping of electrostatic fields in 2D heterostructures

Murthy, A. A.; Ribet, S. M.; Stanev, T. K.; Liu, P.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Stern, N. P.; dos Reis, R.; Dravid, V. P.

A simple pressure-assisted method for MicroED specimen preparation

Zhao, J.; Xu, H.; Lebrette, H.; Carroni, M.; Taberman, H.; Hogbom, M.; Zou, X.

Electron crystallographic investigation of crystals on the mesostructural scale

Mao, W.; Bao, C.; Han, L.

Atomic-number (Z)-correlated atomic sizes for deciphering electron microscopic molecular images

Xing, J.; Takeuchi, K.; Kamei, K.; Nakamuro, T.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Nanodiffraction imaging of polymer crystals

Kanomi, S.; Marubayashi, H.; Miyata, T.; Tsuda, K.; Jinnai, H.

Nikishin, I.; Dulimov, R.; Skryabin, G.; Galetsky, S.; Tchevkina, E.; Bagrov, D.

Lungerich, D.; Hoelzel, H.; Harano, K.; Jux, N.; Amsharov, K. Y.; Nakamura, E.

Lungerich, D.; Hoelzel, H.; Harano, K.; Jux, N.; Amsharov, K. Y.; Nakamura, E.

Intrinsic helical twist and chirality in ultrathin tellurium nanowires

Londoño-Calderon, A.; Williams, D. J.; Schneider, M. M.; Savitzky, B. H.; Ophus, C.; Ma, S.; Zhud, H.; Pettes, M. T.

Direct visualization of the earliest stages of crystallization

Singh, M. K.; Ghosh, C.; Miller, B.; Carter, C. B.

Dual-solvent Li-ion solvation enables high-performance Li-metal batteries

Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Kong, X.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Mackanic, D. G.; Huang, X.; Qin, J.; Bao, Z.; Cui. Y.

Hasegawa, S.; Takano, S.; Harano, K.; Tsukuda, T.

Hasegawa, S.; Takano, S.; Harano, K.; Tsukuda, T.

Rim binding of cyclodextrins in size-sensitive guest recognition

Hanayama, H.; Yamada, J.; Tomotsuka, I.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Graded microstructure preparation in austenitic stainless steel during radial-shear rolling

Lezhnev, S. N.; Naizabekov, A. B.; Panin, E. A.; Volokitina, I. E.; Arbuz, A. S.

Corrosion of lithium metal anodes during calendar ageing and its microscopic origins

Boyle, D. T.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Z.; Cui, Y.

Few-nm-sized, phase-pure Au5Sn intermetallic nanoparticles: synthesis and characterization

Osugi, S.; Takano, S.; Masuda, S.; Harano, K.; Tsukuda, T.

Darling, A. L.; Dahrendorff, J.; Creodore, S. G.; Dickey, C. A.; Blair, L. J.; Uversky, V. N.

Cheng, Q.; Li, Q.; Xu, L.; Jiang, H.

Evolution of anisotropic arrow nanostructures during controlled overgrowth

Wang, W.; Erofeev, I.; Nandi, P.; Yan, H.; Mirsaidov, U.

Local lattice deformation of tellurene grain boundaries by four-dimensional electron microscopy

Londoño-Calderon, A.; J. Williams, D. J.; Schneider, M.; Savitzky, B. H.; Ophus, C.; Pettes, M. T.

Au/TiN nanostructure materials for energy storage applications

Ali, S. M.; Ramay, S. M.; Mahmood, A.; ur Rehman, A.; Ali, G.; Ali, S. D.; Uzzaman, T.

Mapping grains, boundaries, and defects in 2D covalent organic framework thin films

Castano, I.; Evans, A. M.; dos Reis, R,; Dravid, V. P.; Gianneschi, N. C.; Dichtel, W. R.

Sekine, R.; Ravat, P.; Yanagisawa, H.; Liu, C.; Kikkawa, M.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

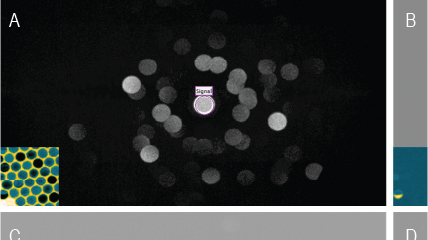

SINGLE: Atomic-resolution structure identification of nanocrystals by graphene liquid cell EM

Reboul, C. F.; Heo, J.; Machello, C.; Kiesewetter, S.; Kim, B. H.; Kim, S.; Elmlund, D.; Ercius, P.; Park, J.; Elmlund, H.

Subramanian, V.; Rodemoyer, B.; Shastri, V.; Rasmussen, L. J.; Desler, C.; Schmidt, K. H.

Hu, S.; Yin, Y.; Chen, B.; Lin, Q.; Tian, Y.; Song, X.; Peng, J.; Zheng, H.; Rao, S.; Wu, G.; Mo, X.; Yan, F.; Chen, J.; Lu, Y.

Capturing the moment of emergence of crystal nucleus from disorder

Nakamuro, T.; Sakakibara, M.; Nada, H.; Harano, K.;Nakamura, E.

4D imaging of soft matter in liquid water

Marchello, G.; De Pace, C.; Acosta-Gutierrez, S.; Lopez-Vazquez, C.; Wilkinson, N.; Gervasio, F. L.; Ruiz-Perez, L.; Giuseppe Battaglia, G.

Greaney, A. J.; Starr, T. N.; Gilchuk, P.; Zost, S. J.; Binshtein, E.; Loes, A. N.; Hilton, S. K.; Huddleston, J.; Eguia, R.; Crawford, K. H. D.; Dingens, A. S.; Nargi, R. S.; Sutton, R. E.; Suryadevara, N.; Rothlauf, P. W.; Liu, Z.; Whelan, S. P. J.; Carnahan, R. H.; Bloom, J. D.

Mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase stalling by remdesivir

Kokic, G.; Hillen, H. S.; Tegunov, D.; Dienemann, C.; Seitz, F.; Schmitzova, J.; Farnung, L.; Siewert, A.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P.

Stabilizing the closed SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer

Juraszek, J.; Rutten, L.; Blokland, S.; Bouchier, P.; Voorzaat, R.; Ritschel, T.; Bakkers, M. J. G.; Renault , L. L. R.; Langedijk, J. P. M.

Development and structural basis of a two-MAb cocktail for treating SARS-CoV-2 infections

Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C.; Gu, C.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, W.; Hong, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Xu, C.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Qiao, W.; Zang, J.; Kong, L.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Qu, D.; Lavillette, D.; Tang, H.; Deng, Q.; Xie, Y.; Cong, Y.; Huang, Z.

Yan, L.; Ge, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guddat, L. W.; Wang, Q.; Rao, Z.; Lou, Z.

Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zheng, W.; Kong, L.; Wang, F.; Zuo, Q.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y.

Spatial mapping of electrostatics and dynamics across 2D heterostructures

Murthy, A. A.; Stanev, T. K.; Ribet, S. M.; Liu, P.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Stern, N. P.; dos Reis, R.; Dravid, V. P.

Mihelc. E. M.; Baker, S. C.; Lanman, J. K.

Yuan, S.; Peng, L.; Park, J. J.; Hu, Y.; Devarkar, S. C.; Dong, M. B.; Shen, Q.; Wu, S.; Chen, S.; Lomakin, I. B.; Xiong, Y.

Zhou, T.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Gorman, J.; Rapp, M.; Cerutti, G.; Chuang, G. -Y.; Katsamba, P. S.; Sampson, J. M.; Schön, A.; Bimela, J.; Boyington, J. C.; Nazzari, A.; Olia, A. S.; Shi, W.; Sastry, M.; Stephens, T.; Stuckey, J.; Teng, I. -T.; Kwong, P. D

Electronically coupled 2D polymer/MoS2 heterostructures

Balch, H. B., Evans, A. M., Dasari, R. R., Li, H., Li, R., Thomas, S., Wang, Q., Bisbey, R. P., Slicker, K., Castano, I., Xun, S., Jiang, L., Zhu, C., Gianneschi, N., Ralph, D. C., Brédas, J-L., Marder, S. R., Dichtel, W. R., Wang, F.

De novo design of potent and resilient hACE2 decoys to neutralize SARS-CoV-2

Linsky, T. W.; Vergara, R.; Codina, N.; Nelson, J. W.; Walker, M. J.; Su, W.; Barnes, C. O.; Hsiang, T. -Y.; Esser-Nobis, K.; Yu, K.; Reneer, B.; Hou, Y. J.; Priya, T.; Mitsumoto, M.; Pong, A.; Lau, Y.; Mason, M. L.; Chen, J.; Chen, A.; Berrocal, T.; Peng, H.; Clairmont, N. S.; Castellanos, J.; Lin, Y. -R..; Josephson-Day, A.; Baric, R. S.; Fuller, D. H.; Walkey, C. D.; Ross, T. M.; Swanson, R.; Bjorkman, P. J.; Gale Jr., M.; Blancas-Mejia, L. M.; Yen, H. -L.; Silva, D. -A.

Yao, H.; Sun, Y.; Deng, Y. -Q.; Wang, N.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, N. -N.; Li, X. -F.; Kong, C.; Xu, Y. -P.; Chen, Q.; Cao, T. -S.; Zhao, H.; Yan, X.; Cao, L.; Lv, Z.; Zhu, D.; Feng, R.; Wu, N.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, R. -R.; Lv, Q.; Sun, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, R.; Yang, G.; Sun, X.; Liu, C.; Lu, X.; Cheng, L.; Qiu, H.; Huang, X. -Y.; Weng, T.; Shi, D.; Jiang, W.; Shao, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, T.; Lang, G.; Qin, C. -F.; Li, L.; Wang, X.

Structure-based development of human antibody cocktails against SARS-CoV-2

Wang, N.; Sun, Y.; Feng, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Y. -Q.; Wang, L.; Cui, Z.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Y. -J.; Li, W.; Zhu, F. -C.; Qin, C. -F.; Wang, X.

Structural analysis of full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein from an advanced vaccine candidate

Bangaru, S.; Ozorowski, G.; Turner, H. L.; Antanasijevic, A.; Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Torres, J. L.; Diedrich, J. K.; Tian, J. -H.; Portnoff, A. D.; Patel, N.; Massare, M. J.; Yates III, J. R.; Nemazee, D.; Paulson, J. C.; Glenn, G.; Smith, G.; Ward, A. B.

Ultrapotent human antibodies protect against SARS-CoV-2 challenge via multiple mechanisms

Tortorici, M. A.; Beltramello, M.; Lempp, F. A.; Pinto, D.; Dang, H. V.; Rosen, L. E.; McCallum, M.; Bowen, J.; Minola, A.; Jaconi, S.; Zatta, F.; De Marco, A.; Guarino, B.; Bianchi, S.; Lauron, E. J.; Tucker, H.; Zhou, J.; Peter, A.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Wojcechowskyj, J. A.; Case, J. B.; Chen, R. E.; Kaiser, H.; Montiel-Ruiz, M.; Meury, M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Spreafico, R.; Dillen, J.; Ng, C.; Sprugasci, N.; Culap, K.; Benigni, F.; Abdelnabi, R.; Foo, S. -Y. C.; Schmid, M. A.; Cameroni, E.; Riva, A.; Gabrieli, A.; Galli, M.; Pizzuto. M. S.; Neyts, J.; Diamond, M. S.; Virgin, H. W.; Snell, G.; Corti, D.; Fink, K.; Veesler, D.;

Architecture of a SARS-CoV-2 mini replication and transcription complex

Yan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, J.; Zheng, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, T.; Jia, Z.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Ra, Z.; Lou, Z.

Du, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, P.; Qi, F.; Wang, G.; Du, X.; Bao, L.; Deng, W.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Nie, J.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, H.; Liu, R.; Gong, S.; Xu, H.; Yisimayi, A.; Qin, C.

Piccoli, L.; Park, Y. -J.; Tortorici, M. A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Walls, A. C.; Beltramello, M.; Silacci-Fregni, C.; Pinto, D.; Rosen, L. E.; Bowen, J. E.; Acton, O. J.; Jaconi, S.; Guarino, B.; Minola, A.; Zatta, F.; Sprugasci, N.; Bassi, J.; Peter, A.; De Marco, A.; Nix, J. C.; Mele, F.; Jovic, S.; Rodriguez, B. F.; Gupta, S. V.; Jin, F.; Piumatti, G.; Presti, G. L.; Pellanda, A. F.; Biggiogero, M.; Tarkowski, M.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Cameroni, E.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Smithey, M.; Hong, D.; Lepori, V.; Albanese, E.; Ceschi, A.; Bernasconi, E.; Elzi, L.; Ferrari, P.; Garzoni, C.; Riva, A.; Snell, G.; Sallusto, F.; Fink, K.; Virgin, H. W.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D.

Guo, L.; Bi, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, W.; Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Cai, X.; Jiang, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, L.; Dang, B.

Cathode-electrolyte interphase in lithium batteries revealed by cryogenic electron microscopy

Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Huang, W.; Chiu, W.

Free fatty acid binding pocket in the locked structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein

Toelzer, C.; Gupta, K.; Yadav, S. K. N.: Borucu, U.; Davidson, A. D.; Williamson, M. K.; Shoemark, D. K.; Garzoni, F.; Staufer, O.; Milligan, R.; Capin, J.; Mulholland, A. J.; Spatz, J.; Fitzgerald, D.; Berger, I.; Schaffitzel, C.

An ultrapotent synthetic nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by stabilizing inactive spike

Schoof, M.; Faust, B.; Saunders, R. A.; Sangwan, S.; Rezelj, V.; Hoppe, N.; Boone, M.; Billesbølle, C. B.; Puchades, C.; Azumaya, C. M.; Kratochvil, H. T.; Zimanyi, M.; Deshpande, I.; Liang, J.; Dickinson, S.; Nguyen, H. C.; Chio, C. M.; Merz, G. E.; Thompson, M. C.; Diwanji, D.; Schaefer, K.; Anand, A. A.; Dobzinski, N.; Zha, B. S.; Simoneau, C. R.; Leon, K.; White, K. M.; Chio, U. S.; Gupta, M.; Jin, M.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Bulkley, D.; Sun, M.; Smith, A. M.; Rizo, A. N.; Moss, F.; Brilot, A. F.; Pourmal, S.; Trenker, R.; Pospiech, T.; Gupta, S.; Barsi-Rhyne, B.; Belyy, V.; Barile-Hill, A. W.; Nock, S.; Liu, Y.; Krogan, N. J.; Ralston, C. Y.; Swaney, D. L.; García-Sastre, A.; Ott, M.; Vignuzzi, M.; QCRG Structural Biology Consortium; Walter, P.; Manglik, A.

Custódio, T. F.; Das, H.; Sheward, D. J.; Hanke, L.; Pazicky, S.; Pieprzyk, J.; Sorgenfrei, M.; Schroer, M. A.; Gruzinov, A. Y.; Jeffries, C. M.; Graewert, M. A.; Svergun, D. I.; Dobrev, N.; Remans, K.; Seeger, M. A.; McInerney, G. M.; Murrell, B.; Hällberg, B. M.; Löw, C.

The architecture of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 with postfusion spikes revealed by cryo-EM and cryo-ET

Liu, C.; Mendonça, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Shen, C.; Liu, J.; Ni, T.; Ju, B.; Liu, C.; Tang, X.; Wei, J.; Ma, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, P.; Zhang, P.

Zhou, T.; Teng, I. -T.; Olia, A. S.; Cerutti, G.; Gorman, J.; Nazzari, A.; Shi, W.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Katsamba, P. S.; Petrova, Y.; Banach, B. B.; Fahad, A. S.; Liu, L.; Lopez Acevedo, S. N.; Madan, B.; de Souza, M. O.; Pan, X.; Wang, P.; Wolfe, J. R.; Yin, M.; Ho, D. D.; Phung, E.; DiPiazza, A.; Chang, L. A.; Abiona, O. M.; Corbett, K. S.; DeKosky, B. J.; Graham, B. S.; Mascola, J. R.; Misasi, J.; Ruckwardt, T.; Sullivan, N. J.; Shapiro, L.; Kwong, P. D.

Kratish, Y.; Nakamuro, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Tomotsuka, I.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.; Marks, T. J.

InsteaDMatic: Towards cross-platform automated continuous rotation electron diffraction

Roslova, M.; Smeets, S.; Wang, B.; Thersleff, T.; Xu, H.; Zou, X.

In situ TEM study of crystallization and chemical changes in an oxidized uncapped Ge2Sb2Te5 film

Singh, M. K.; Ghosh, C.; Miller, B.; Kotula, P. G.; Tripathi, S.; Watt, J.; Bakan, G.; Silva, H.; Carter, C. B.

Inside polyMOFs: Layered structures in polymer-based metal–organic frameworks

Bentz, K. C., Gnanasekaran, K., Bailey, J. B. Ayala, S., Tezcan, F. A., Gianneschi, N. C., Cohen, S. M.

Aryl radical addition to curvatures of carbon nanohorns for single-molecule level molecular imaging

Kamei, K.; Shimizu, T.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Kim, Y. -J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, K.; Kwon, O. -H.

Effect of adventitious carbon on pit formation of monolayer MoS2

Park, S.; Siahrostami, S.; Park, J.; Mostaghimi, A. H. B.; Kim, T. R.; Vallez, L.; Gill, T. M.; Park, W.; Goodson, K. E.; Sinclair, R.; Zheng, X.

Stuckner, J.; Shimizu, T.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.; Murayama, M.

Gnanasekaran, K., Vailonis, K. M., Jenkins, D. M., Gianneschi, N. C.

Langer, L. M.; Gat, Y.; Bonneau, F.; Conti, E.

Shimizu, T.; Lungerich, D.; Stuckner, J.; Murayama, M.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Decoding the stoichiometric composition and organisation of bacterial metabolosomes

Yang, M.; Simpson, D. M.; Wenner, N.; Brownridge, P.; Harman, V. M.; Hinton, J. C. D.; Beynon, R. J.; Liu , L. -N.

1D to 2D transition in tellurium observed by 4D electron microscopy

Londoño-Calderon, A.; Williams, D. J.; Ophus, C.; Pettes, M. T.

Murthy, A. A.; Stanev, T. K.; dos Reis, R.; Hao, S.; Wolverton, C.; Stern, N. P.; Dravid, V. P.

Unveiling the microscopic origins of phase transformations: An in situ TEM perspective

Yu, L.; Hudak, B. M.; Ullah, A.; Thomas, M. P.; Porter, C. C.; Thisera, A.; Pham, R. H.; Goonatilleke, M. D. A.; Guiton, B. S.

Ogata, A. F.; Rakowski, A. M.; Carpenter, B. P.; Fishman, D. A.; Merham, J. G.; Hurst, P. J.; Patterson, J. P.

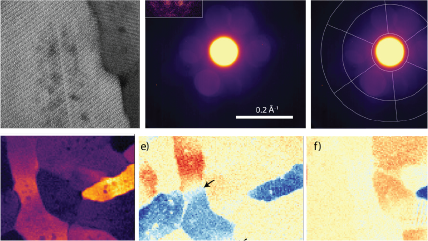

Thickness and defocus dependence of inter-atomic electric fields measured by scanning diffraction

Addiego, C.; Gao, W.; Pan, X.

Errokh, A.; Magnin, A.; Putaux, J. -L.; Boufi, S.

Nam, K. W.; Park, S. S.; dos Reis, R.; Dravid, V. P. Kim, H.; Mirkin, C. A.; Stoddart, J. F.

Gao, W.; Addiego, C.; Wang, H,; Yan, X.; Hou, Y.; Ji, D.; Heikes, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Huyan, H.; Blum, T.; Aoki, T.; Nie, Y.; Schlom, D.; Wu, R.; Pan, X.

Buffin, S.; Peubez, I.; Barrière, F.; Nicolaï, M., -C.; Tapia, T.; Dhir, V.; Forma, E.; Sève, N.; Legastelois, I.

Recent progress of in situ transmission electron microscopy for energy materials

Chao Zhang, C.; Firestein, K. L.; Fernando, J. F. S.; Siriwardena, D.; von Treifeldt, J. E.; Golberg, D.

Electron microdiffraction reveals the nanoscale twist geometry of cellulose nanocrystals

Ogawa, Y.

Atomistic structures and dynamics of prenucleation clusters in MOF-2 and MOF-5 syntheses

Xing, J.; Schweighauser, L.; Okada, S.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Quantifying inactive lithium in lithium metal batteries

Fang, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Lee, J. Z.; Lee, L. M. -H.; Alvarado, J.; Schroeder, M. A.; Yang, Y.; Lu, B.; Williams, N.; Ceja, M.; Yang, L.; Cai, M.; Gu, J.; Xu, K.; Wang, X.; Meng, Y. S.

Improved applicability and robustness of fast cryo-electron tomography data acquisition

Eisenstein, F.; Danev, R.; Pilhofer, M.

Solving a new R2lox protein structure by microcrystal electron diffraction

Xu, H.; Lebrette, H.; Clabbers, M. T. B.; Zhao, J.; Griese, J. J.; Zou, X.; Hogbom, M.

Li, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Cha, D.; Zheng, X.; Yousef, A. A.; Song, K.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Han, Y.

Formation of two-dimensional transition metal oxide nanosheets with nanoparticles as intermediates

Yang, J.; Zeng, Z.; Kang, J.; Betzler, S.; Czarnik, C.; Zhang, X.; Ophus, C.; Yu, C.; Bustillo, K.; Pan, M.; Qiu, J.; Wang, L. -W.; Zheng, H.

Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Guan, L.; Cao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Jin, C.

Mechanism of stress induced crystallization of polyethylene

Yakovlev, S.; Fiscus, D.; Brant, P.; Butler, J.; Bucknall, D. G.; Downing, K. H.

Cryo-EM structures of atomic surfaces and host-guest chemistry in metal-organic frameworks

Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, W.; Sinclair, R.; Chiu, W.; Cui, Y.

Single particle cryo-EM reconstruction of 52 kDa streptavidin at 3.2 Angstrom resolution

Fan, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J. -C.; Zhao, L.; Peng, H. -L.; Lei, J.; Wang, H. -W.

Su, T.; Hood, Z. D.; Naguib, M.; Bai, L.; Luo, S.; Rouleau, C. M.; Ivanov, I. N.; Ji, H.; Qin, Z.; Wu, Z.

Thermal stability and irradiation response of nanocrystalline CoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy

Zhang, Y.; Tunes, M. A.; Crespillo, M. L.; Zhang, F.; Boldman, W. L.; Rack, P. D.; Jiang, L.; Xu, C.; Greaves, G.; Donnelly, S. E.; Wang, L.; Weber, W. J.

Tunes, M. A.; Harrison, R. W.; Donnelly, S. E.; Edmondson, P. D.

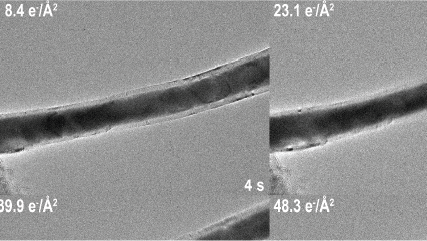

Factors affecting electron beam damage in calcite nanoparticles

Hooley, R.; Brown, A.; Brydson, R.

Low dose scanning transmission electron microscopy of organic crystals by scanning moiré fringes

S’ari, M.; Cattle, J.; Hondow, N.; Brydson, R.; Brown, A.

A 3.8 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of a small protein bound to an imaging scaffold

Liu, Y.; Huynh, D. T.; Yeates, T. O.

In situ structures of polar and lateral flagella revealed by cryo-electron tomography

Zhu, S.; Schniederberend, M.; Zhitnitsky, D.; Jain, R.; Galán, J. E.; Kazmierczak, B. I.; Liu, J.

Carbon polyaniline capacitive deionization electrodes with stable cycle life

Evans, S. F.; Ivancevic, M. R.; Wilson, D. J.; Hood, Z. D.; Adhikari, S. P.; Naskar, A. K.; Tsouris, C.; Paranthaman, M. P.

Le Ferrand, H.; Duchamp, M.; Gabryelczyk, B.; Cai, H.; Miserez, A.

Off-axis electron holography for imaging the magnetic behavior of vortex-state minerals

Almeida, T. P.; Muxworthy, A. R.; Williams, W.; Kasama, T.; Kovács, A.; Dunin-Borkowski, R. E.

Connolly, M.; Zhang, Y.; Mahri, S.; Brown, D. M.; Ortuño, N.; Jordá-Beneyto, M.; Maciaszek, K.; Stone, V.; Fernandes, T. F.; Johnston, H. J.

Mechanical response of gasoline soot nanoparticles under compression: An in situ TEM study

Jenei, I. Z.; Dassenoy, F.; Epicier, T.; Khajeh, A.; Martinic, A.; Uy, D.; Ghaednia, H.; Gangopadhyay, A.

2D/2D heterojunction of Ti3C2/g-C3N4 nanosheets for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution

Su, T.; Hood, Z. D.; Naguib, M.; Bai, L.; Luo, S.; Rouleau, C. M.; Ivanov, I. N.; Ji, H.; Qin, Z.; Wu, Z.

Rodriguez-Caro, H.; Dragovic, R.; Shen, M.; Dombi, E.; Mounce, G.; Field, K.; Meadows, J.; Turner, K.; Lunn, D.; Child, T.; Southcombe, J. H.; Granne, I.

Nanoscale mosaicity revealed in peptide microcrystals by scanning electron nanodiffraction

Gallagher-Jones, M.; Ophus, C.; Bustillo, K. C.; Boyer, D. R.; Panova, O.; Glynn, C.; Zee, C., -T.; Ciston, J.; Mancia, K. C.; Minor, A. M.; Rodriguez, J. A.

Unconventional magnetization textures and domain-wall pinning in Sm--Co magnets

Pierobon, L.; Kovács, A.; Schäublin, R. E.; Wyss, U.; Dunin-Borkowski, R. E.; Löffler, J. F.; Charilaou, M.

Structural analysis of single nanoparticles in liquid by low-dose STEM nanodiffraction

Khelfa, A.; Byun, C.; Nelayah, J.; Wang, G.; Ricolleau, C.; Alloyeau, D.

Surface crystallization of liquid Au–Si and its impact on catalysis

Panciera, F.; Tersoff, J.; Gamalski, A. D.; Reuter, M. C.; Zakharov, D.; Stach, E. A.; Hofmann, S.; Ross, F. M

Layered-structure SbPO4/reduced graphene oxide: An advanced anode material for sodium ion batteries

Pan, J.; Chen, S.; Fu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, N.; Gao, P.; Yang, J.; Qian, Y.

2D transition metal carbides (MXenes) for carbon capture

Persson, I.; Halim, J.; Lind, H.; Hansen, T. W.; Wagner, J. B.; Näslund, L. -A.; Darakchieva, V.; Palisaitis, J.; Rosen J.; Persson, P. O. A.

2D transition metal carbides (MXenes) for carbon capture

Persson, I.; Halim, J.; Lind, H.; Hansen, T. W.; Wagner, J. B.; Näslund, L. -A.; Darakchieva, V.; Palisaitis, J.; Rosen J.; Persson, P. O. A.

Gao, W.; Wu, J.; Yoon, A.; Lu, P.; Qi, L.; Wen, J.; Miller, D. J.; Mabon, J. C.; Wilson, W. L.; Yang, H.; Zuo, J. -M.

Atomic step flow on a nanofacet

Harmand, J. -C.; Patriarche, G.; Glas, F.; Panciera, F.; Florea, I.; Maurice, J. -L.; Travers, L.; Ollivier, Y.

A high-entropy alloy with hierarchical nanoprecipitates and ultrahigh strength

Fu, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wardini, J. L.; MacDonald, B. E.; Wen, H.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Rupert, T. J.; Chen, W.; Lavernia, E. J.

Pan, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, D.; Xu, X.; Sun, Y.; Tian, F.; Gao, P.; Yang, J.

Jung, H. J.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Park, J.; Dravid, V. P.; Shin, B.

In situ kinetic and thermodynamic growth control of Au–Pd core–shell nanoparticles

Tan, S. F.; Bisht, G.; Anand, U.; Bosman, M.; Yong, X. E.; Mirsaidov, U.

Yasin, F. S.; Harvey, T. R.; Chess, J. J.; Pierce, J. S.; Ophus, C.; Ercius, P.; McMorran, B. J.

Zeng, L.; Gammer, C.; Ozdol, B.; Nordqvist, T.; Nygård, J.; Krogstrup, P.; Minor, A. M.; Jäger, W.; Olsson, E.

Yu, J.; Yuan, W.; Yang, H.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.

Refinement and analysis of the mature Zika virus cryo-EM structure at 3.1 Å resolution

Sevvana, M.; Long, F.; Miller, A. S.; Klose, T.; Buda, G.; Sun, L.; Kuhn, R. J.; Rossmann, M. G.

Fernandez, S.; Ostraat, M. L.; Lawrence III, J. A.; Zhang, K.

Local nanoscale strain mapping of a metallic glass during in situ testing

Gammer, C.; Ophus, C.; Pekin, T. C.; Eckert, J.; Minor, A. M.

Xu, H. Lebrette, H.; Yang, T.; Hovmoller, S.; Hogbom, M.; Zou, X.

Hepp, S. E.; Borgo, G. M.; Ticau, S.; Ohkawa, T.; Welch, M. D.

Nanoparticle interactions guided by shape‐dependent hydrophobic forces

Tan, S. F.; Raj, S.; Bisht, G.; Annadata, H. V.; Nijhuis, C. A.; Král, P.; Mirsaidov, U.

Lutz, L.; Dachraoui, W.; Demortière, A.; Johnson, L. R.; Bruce∥, P. G.; Grimaud, A.; Tarascon, J. -M.

Destefani, T. A.; Onaga, G. L.; de Farias, M. A.; Percebom, A. M.; Sabadini, E.

Andrew, R. S.; Austin, B. F.; George, C. R.; Ronald, C. B.; James, M. J.

S.E.Gilliland III, Tengco, J. M. M.; Yang, Y.; Regalbuto, J. R.; Castano, C. E.; Gupton, B. F.

In situ nanobeam electron diffraction strain mapping of planar slip in stainless steel

Pekin, T. C.; Gammer, C.; Ciston, J.; Ophus, C.; Minor, A. M.

Direct microscopic analysis of individual C60 dimerization events: Kinetics and mechanisms

Okada, S.; Kowashi, S.; Schweighauser, L.; Yamanouchi, K.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.

Atomic structure of sensitive battery materials and interfaces revealed by cryo–electron microscopy

Li, Y.; Li.; Y.; Pei, A.; Yan, K.; Sun, Y.; Wu, C. -L; Joubert, L. -M.; Chin, R.; Koh, A. L.; Yu, Y.; Perrino, J.; Butz, B.; Chu, S.; Cui, Y.

Vertical graphene growth on SiO microparticles for stable lithium ion battery anodes

Shi, L.; Pang, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Tan, Z.; Gao, P.; Ren, J.; Huang. Y.; Peng, H.; Liu, Z.

Koh, A. L.; Gidcumb, E.; Zhou, O.; Sinclair, R.

Lear, P. V.; González-Touceda, D.; Couto, B. P.; Viaño, P.; Guymer, V.; Remzova, E.; Tunn, R.; Chalasani, A.; García-Caballero, T.; Hargreaves, I. P.; Tynan, P. W.; Christian, H. C.; Nogueiras, R.; Parrington, J.; Diéguez, C.

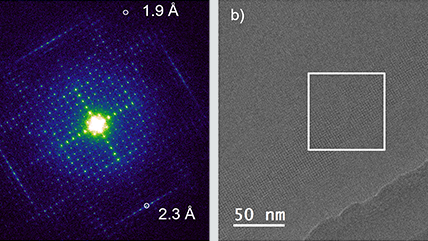

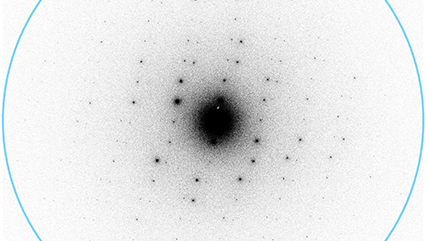

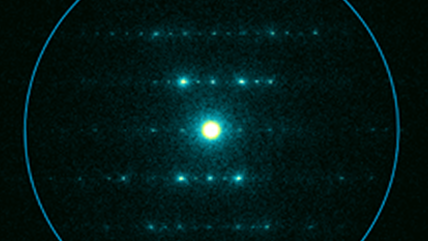

Nyquist frequency

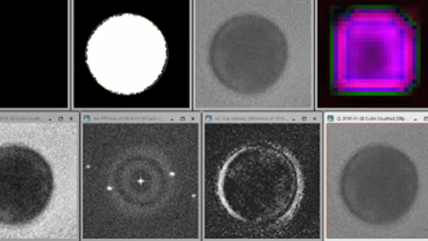

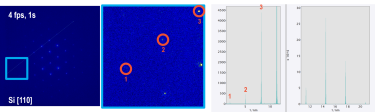

Dose fractionation and motion correction

Improving DQE with counting and super-resolution